Jason Anderson

The first of 2 articles on the 3-stage lesson planning model that I propose has just been published in the IATEFL Teacher Education Newsletter. In the article I argue that CAP is more appropriate and more relevant for today’s teaching and teacher education courses than alternatives such as PPP, ESA, etc. It’s also the topic I’ll be talking on at IATEFL Glasgow 2017 (scroll down for details).

- Click here to read the article.

I also provide a little initial data from trainee teachers who found it useful, offer example CAP lesson skeletons from my forthcoming book the Trinity CertTESOL Companion and also link it to text-based language teaching, an approach that is fairly well established in Australia, but still poorly known in the UK.

What are the three phases of CAP?

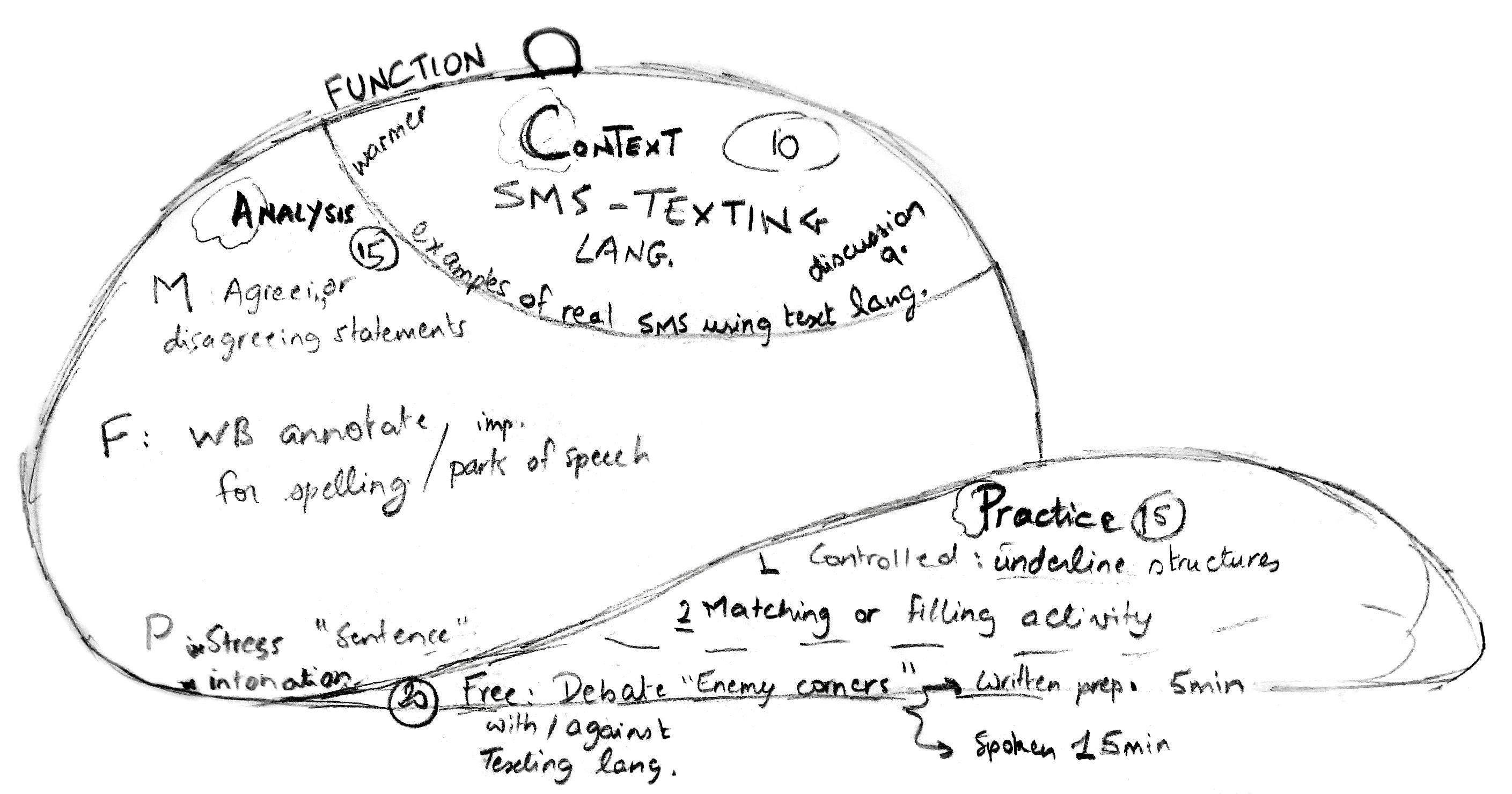

The three phases of CAP are simple, logical and easy to remember as follows:

Context

The context for learning is established through a text (listening, reading or video), a presented ‘situation’ (in the classroom or through audio-visual resources), or the involvement of learners. This may be accompanied by activities that raise background schemata, check comprehension, or engage learners meaningfully in the text.

Analysis

Language features are noticed and analysed explicitly for meaning, form, pronunciation and usage/use as appropriate. This may include grammatical, functional, lexical or textual aspects of the language. This is roughly equivalent to Harmer’s Study stage or Scrivener’s Clarification.

Practice

Learners practise using the language. This may include controlled and freer speaking or writing practice of the language analysed, scaffolded and independent text construction or a communicative task.

An optional 4th stage, turns ‘CAP’ to CAPE’:

Evaluation

When practice involves text construction, self-, peer and teacher evaluation of the text are possible, such as in a gallery walk activity after a writing task or performance of role plays for the class.

There are possibility for changing and adapting the model, depending on lesson type and context. As always in the article, I offer it as a scaffolding tool, not a rule or dogma.

More on CAP

A second article on CAP is due out later this year, where I explore changes in how coursebooks have provided context over the last 30 years, offer compelling evidence that they also support a C-A-P model, and explore ways the model can be adapted to suit different lesson shapes and theories of teaching and learning.

CAP and ESA

Several colleagues have asked me to clarify exactly how CAP is different from Harmer’s ESA (Engage, Study, Activate). Here are three fundamental differences:

- In Harmer’s model, as described in ‘How to teach English’ from 1998, there is no reference to context or contextualisation in his description of the Engage lesson stage. While he mentions activities that could be used to contextualise new language, Harmer’s main interest here is in the affective involvement of the learner in the lesson, something that cannot be underestimated, especially at primary and secondary levels, when they may not yet have any intrinsic motivation to learn English. However, as one trainee teacher once said to me: ‘Shouldn’t all the lesson be engaging?’, highlighting a potential weakness in the model and perhaps revealing a confusion of affective and structural concerns. In CAP, the primary focus of the Context stage is obviously to provide a clear context for the new language.

- In Harmer’s ESA, controlled practice activities fall under the Study stage, which is logical, given his choice of terms. However, in reality (and in the coursebooks I analysed during my research for this model) there is a continuum from more controlled to freer practice activities, making it sometimes difficult for trainee teachers and even their tutors to categorise an activity. Ultimately, how we categorise an activity can depend on how it’s done, the role we perceive it having in the lesson, and even our personal assumptions regarding theories of language learning. In CAP, all practice falls under the practice stage. The model reflects the fact that coursebooks (without exception in my research) always provide opportunities for practice of the language analysed, but that this isn’t necessarily either a combination of more and less controlled practice, simply some kind of practice.

- ‘Activate’ is a beautiful word, but in reality it implies a particular type of free practice that carries connotations of interaction between learners, especially in spoken form. Despite the fact that Harmer makes it clear in his description of the model that it does include certain receptive skills and writing activities, trainees also often find it difficult to understand when a reading or listening activity is ‘activate’ and when it is ‘study’. They also tend to overlook writing, the importance of which - in the current IT-mediated era - cannot be denied. The word Practice in my model is intended to be descriptive and unambiguous - learners practise using the language in some way. Thus, it’s compatible with a range of approaches, cultural perceptions about learning and doesn’t implicitly prioritise spoken interaction, which cannot necessarily be said about ‘Activate’.

When developing the CAP model, I was very careful to choose words that are as descriptive and unambiguous as possible, precisely due to problems that I and colleagues have had with misunderstandings of terms in other models. In selecting ‘context’, ‘analysis’ and ‘practice’ as the three core stages, I tried to ensure that the meanings of the words remain unchanged from typical dictionary definitions, so that they retain their everyday sense in their pedagogic usage, thereby enabling prior (linguistic) knowledge to inform and scaffold learning of how to structure a lesson.

Link nội dung: https://khoaqhqt.edu.vn/cap-english-a60444.html