We don’t know how many people in Gaza have perished from starvation and related health crisis. But we have good reason to fear that the toll will be high.

The humanitarian data for Gaza are poor and inference from the existing data to a death toll is a hazardous exercise with a wide margin for error, as this paper will show. However, absence of evidence is not evidence for absence. Israel and defenders of Israel have criticized the Integrated food security Phase Classification (IPC) data and analysis, but the alternative data and analysis they have put forward do not add up to a refutation. What Israel needs to do is to facilitate high quality data gathering by humanitarian agencies, to provide an accurate determination of levels of suffering and needs.

This paper covers the following: (a) the question of what is included in excess mortality in humanitarian emergencies; (b) methods for estimating mortality in these circumstances; (c) some estimates for mortality derived from these approaches; and (d) how Gaza’s humanitarian emergency compares to others.

The paper avoids the controversy over whether the label ‘famine’ is appropriate, focusing instead on the broader question of deaths attributable to starvation and related causes. The balance of evidence is that people are perishing of starvation and related health crises and many more will do so without immediate and effective humanitarian action and restoration of essential services.

If Israel and its advocates seek to challenge this claim they need to provide better data including by enabling international humanitarian agencies to conduct the necessary high-quality surveys. Until then, the precautionary principle for humanitarian assessment counsels us to act on the basis of the more alarming projections.

Background Observations

It’s important to be clear about the meaning of ‘starvation’ and what is meant by excess mortality in starvation-related crises. Starvation is transitive and intransitive, individual (biological) and collective (related to the population or community ecology).

The act of starvation (the transitive sense) is defined in law as ‘deprivation of objects indispensable to survival’.[1] Note that this includes not only food, but also water, sanitation, medicine, shelter, maternal care for young children, and a host of other essentials. Note also that impeding relief assistance is not the primary element in the crime. This definition reflects the empirical facts about elevated mortality in starvation-driven crises.

Starvation is also a state of affairs (in its intransitive sense). At an individual level, starvation is both the physical, medical condition of life-threatening severe acute malnutrition, and the increased susceptibility of a malnourished individual to falling sick and dying from disease and dehydration.

At a collective level, starvation is more complicated. First, note that it is a failure to consume adequate food, not insufficiency of food in toto. As stated succinctly by the eminent economist Amartya Sen, ‘Starvation is the characteristic of some people not having enough food to eat. It is not the characteristic of there not being enough food to eat.’[2] There is a common misapprehension among non-specialists that famine or mass starvation are constituted by food shortage and overcome solely by better food availability.

At a collective level, starvation-related mortality is driven not only by malnutrition and increased susceptibility of the malnourished to disease, but also by health crisis including increased exposure to disease. This was put succinctly by the pioneering nutritionist Wallace Akroyd:

Famine has often been associated with outbreaks of disease which have killed many more people than starvation itself. But this association is in the main social rather than physiological, i.e., it is due to the disruption of the society, facilitating the spread of epidemic disease, rather than lowered bodily resistance to invading organisms.’[3]

Historic accounts of famine are replete with ‘famine fevers’ including inter alia typhus, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, measles, and smallpox.[4] Indeed, in these crises ‘the question is not “will there be an epidemic?” but rather “what will be the agent?”[5]

One important implication of this is that the value of food aid in reducing mortality is not only increasing food consumption but also in enabling people to remain in their homes, preserving their assets, livelihoods and social capital, and minimizing the risk of outbreaks of communicable diseases. Another implication is that attention to water, sanitation, vaccination and other health services is no less important to preventing mortality. All of these lessons are well-established.

Famines vary in the proportion of deaths attributed to malnutrition as such and to communicable diseases made more prevalent and more lethal by disruption of society. Physicians’ diagnoses of starvation deaths also vary according to their professional training and the autopsy protocols they use. It is not uncommon for a food emergency to have a very small number of deaths diagnosed as due to malnutrition or starvation alongside a doubling or trebling of overall mortality due to health crisis factors. A case in point is Syria.[6]

Mortality in such crises can be assessed as either: (a) aggregate mortality; (b) excess mortality over a baseline; (c) excess mortality over a baseline attributed to causes other than violent trauma; or (d) mortality specifically attributed to malnutrition.

Measuring famine mortality also requires a figure for the baseline crude death rate (CDR). The IPC thresholds were developed with the populations of north-east Africa in mind. Historic famines occurred against a CDR that was far higher. The emergencies in Syria and Gaza take place against baseline CDRs that are considerably lower.

Mass starvation mortality can also be approached from the perspective of the wider human costs of war. Large scale violence causes massive disruption and displacement, which, deliberately or otherwise, in turn contribute to starvation and health crisis. This question became particularly salient after the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Studies in Iraq highlight the difficulties of obtaining a reliable body count for violent (trauma) deaths, and the variability of the ratio between direct and indirect deaths depending on circumstances, methods and timing.[7] Some episodes in Iraq, for example Falluja in 2004, have ratios of 2 direct deaths to every one indirect death, but in general the ratios lean towards 1:1.5 or higher. Another case for which the data have been carefully scrutinized is Darfur, Sudan, in 2003-05, for which the best evidence indictes a ratio of 1:2.3.[8] Comparison across numerous cases provides widely varying ratios, depending on a range of factors.[9] The largest datasets imply ratios of between 1:1.18 and 1:4, but with outliers in either direction, including the extreme case of the Democratic Republic of Congo of 1:15.[10]

Methods for Estimating Aggregate Mortality

This section briefly examines some of the methods that can be used to estimate mortality, and the availability of datapoints for the situation in Gaza following October 7, 2023.[11]

SMART surveys: The best quality humanitarian data are surveys conducted according to the protocols of the Standardized Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions (SMART). They are the preferred data source for the IPC. Where these surveys are lacking, the IPC famine review committee is reluctant to conclude that mortality thresholds have been breached sufficient to determine IPC 5 ‘famine.’

Demographic surveys and census data. These are the parable’s autopsy: the post-hoc ascertainment of mortality over the recent past. There are no such data from Gaza.

Physician diagnoses. Diagnoses of malnutrition, or malnutrition with complications, as a cause of death, are an indicator of severe food emergency and are useful datapoints for validating other indicators for starvation. The number of such diagnoses is commonly an undercount of malnutrition-related mortality by at least one order of magnitude.

On the basis of reports from the Gaza Ministry of Health, the WHO reported 32 deaths diagnosed as due to severe acute malnutrition up to June 6, 2024,[12] after which they stopped reporting these data. At that time it reported a total of 73 patients admitted to hospital with severe acute malnutrition with complications. On December 4, 2024, 394 patients were reported as admitted with severe acute malnutrition with complications.[13] If the case fatality ratio is unchanged this implies 173 deaths.

Evidence for higher figures comes from a survey of 65 doctors, nurses and paramedics who worked in Gaza after October 2023. Of these, 63 observed severe malnutrition in patients, health care workers and the general population. Of these 33, worked with newborns, and 25 of them saw babies who had been born healthy return to hospitals and die from dehydration, starvation or infections caused by their malnourished mothers’ inability to breastfeed and a lack of infant formula and clean water.[14]

Inference from IPC phases. The IPC draws upon a variety of sources including sample surveys. In the case of Gaza it has several datapoints but no SMART surveys.

IPC phase 4 assumes a crude death rate (CDR) of more than 1/10,000/day (and less than 2/10,000/day) or twice the reference (background) level. IPC 5 (‘famine’ or ‘catastrophe’) assumes a CDR of 2/10,000/day or more. Noting that the IPC produced estimates for the number of people in IPC 4 and 5, and the length of time they are in these phases, it is an elementary arithmetical exercise to generate a putative mortality figure. The IPC discourages this. First, there is an ambiguity over objective versus relative levels of mortality, and (relatedly) the baseline CDR needs to be factored in. Second, the timing (sequencing) of food insecurity, malnutrition and mortality is not simple (see below). Third, there are many factors intervening between the IPC indicators and elevated CDR. That said, using arithmetic derivation from IPC figures to derive estimates for CDRs in South Sudan indicates aggregate all-cause mortality numbers broadly similar to those estimated from other sources.[15]

A group of 99 physicians and nurses wrote an open letter to President Joe Biden that used this method to estimate 62,400 deaths up to September 30, 2024.[16] They attribute such mortality to ‘starvation and its complications’ but cite appropriate caveats.

Food availability. Mass starvation can occur without food availability decline or shortage, and food availability can fluctuate without causing mass starvation. Food availability-based calculations can lead to vast variations in mortality projections.[17] There are many reasons why calculating calorific values is not a good measure for projecting mortality. First, it is usually only a minority of a population that faces starvation, and that is due to their absolute poverty and/or exclusion from formal or informal systems of food allocation. Famines may strike when the shops are well-stocked and often do. The starving simply do not have the money to buy food, and lack the means to earn that money. Second, in any emergency relief program, it is the ‘last mile’ of distribution that matters. People may starve while food is in warehouses nearby or held at roadblocks: the food may not get to them, or they may not be able to get to it. Third, the key factor driving mortality may be social disruption and health crisis. Lastly, there are often alternative unmeasured ‘famine foods’ and other hidden resources that complicate inference from theoretically available calories to calorie consumption by the most vulnerable.

A group of Israeli physicians used estimates for food deliveries to challenge the IPC findings in 2024.[18] This was challenged on analytical, empirical and methodological grounds and cannot be considered credible.[19] Better figures for food availability have been calculated.[20]

Health crisis scenarios. Epidemiologists have sought to construct models for how mortality patterns will change as the key elements of health infrastructure and the ecology of health, disease and nutrition are disrupted. Some elements of this are relatively straightforward, such as the predictable increase in neo-natal deaths due to lack of specialized care facilities and likely mortality among patients reliant on particular medication, e.g. for cancer, diabetes or heart conditions. Others are much more complex, such as the possibility of outbreaks of communicable diseases. Such models are dependent upon the assumptions in the scenarios on which they are built and provide a range of possible outcomes rather than a prediction.

A group of epidemiologists developed scenarios for Gaza for the period February to August 2024, under scenarios of ‘ceasefire’, ‘status quo’ and ‘escalation’, with and without epidemics, with a range of figures.[21] The full range of projected figures is 4,200-259,680 including traumatic deaths. Selected figures for non-traumatic deaths are as follows: Without epidemics scenarios, median figures: ceasefire: 3,300; status quo, 4,810; escalation: 5,730; with epidemics: ceasefire: 5,030; status quo: 8,470; escalation: 11,460. The value of this exercise lies particularly in illustrating the wide range of possible outcomes and the factors determining such variation.

Ratio methods. Epidemiologists and demographers have derived estimates for the ratio between the numbers of people killed in ‘direct’ violence and ‘indirect’ deaths from hunger, disease and health crisis. The ratios range widely and tend to rise over the timeline of the crisis in question. In Gaza, the most recent figure for direct deaths is 44,580, as reported by the Ministry of Health and WHO on December 4, 2024.[22] That report also mentions an estimated 10,000 people ‘reported missing under the rubble,’ which if included, would increase the ratio method estimates proportionally.

Baseline mortality for the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the three years 2020-2022 was 3.4/1,000/year.[23] The population of Gaza was 2.14 million. This implies that in the absence of armed conflict, mortality in the 12 months from October 7, 2023 would have been 7,276 and in the 14 months to December 6, 2024, it would have been 8,489. The relevant numbers should be subtracted from aggregate mortality estimates in the table below.

Non-trauma mortality estimates for Gaza

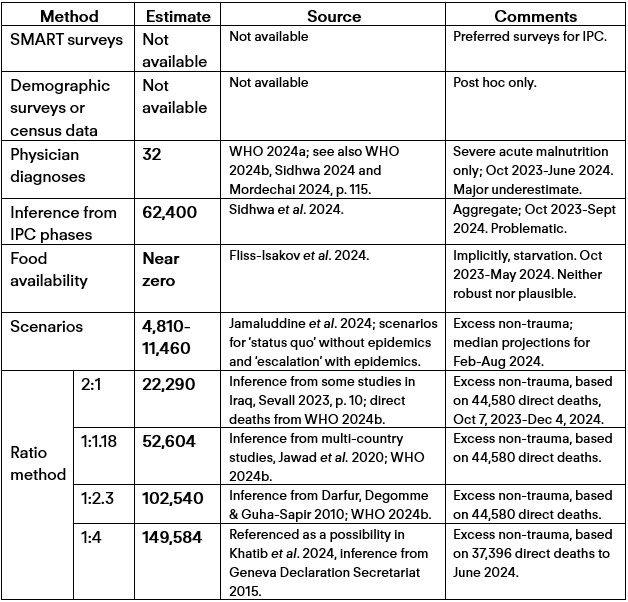

The following table indicates the range of estimates for the numbers who have died on account of mass starvation or humanitarian emergency in Gaza after October 7, 2023. Note that the estimates are for different overall figures: aggregate, excess non-trauma, and caused by severe acute malnutrition (starvation).

Table 1: Estimates for non-trauma mortality in Gaza

Three conclusions can be drawn from this table. The first is that the range of estimates is remarkable. The second is that the low-end estimates can be discounted, and the high-end ones treated with extreme caution. However, figures of 10,000 or more deaths caused by starvation and health crisis/social disruption can be considered a credible estimate of what is occurring. The third is that there is an urgent and imperative need for better data.

Gaza Compared to Other Recent Humanitarian Emergencies

The question of whether there is ‘famine’ according to the IPC definition, or not, has distracted attention from the scale of the humanitarian emergency in Gaza. A better way of assessing the level of emergency and likely scale of mortality is by comparing it with other cases reviewed by the IPC famine review committee since it was established in 2014,[24] and Somalia which was assessed using the IPC methodology in 2011 and where famine was declared,[25] and Darfur in 2003-05, for which we have a good indication of the sequencing of direct (violent trauma) deaths and indirect (hunger and disease) deaths.

The rationale for this comparison is that we can expect a rough correlation between the combined magnitude and severity of emergencies and mortality, taking into account duration (sequencing and trajectory).

Magnitude and Severity Comparisons

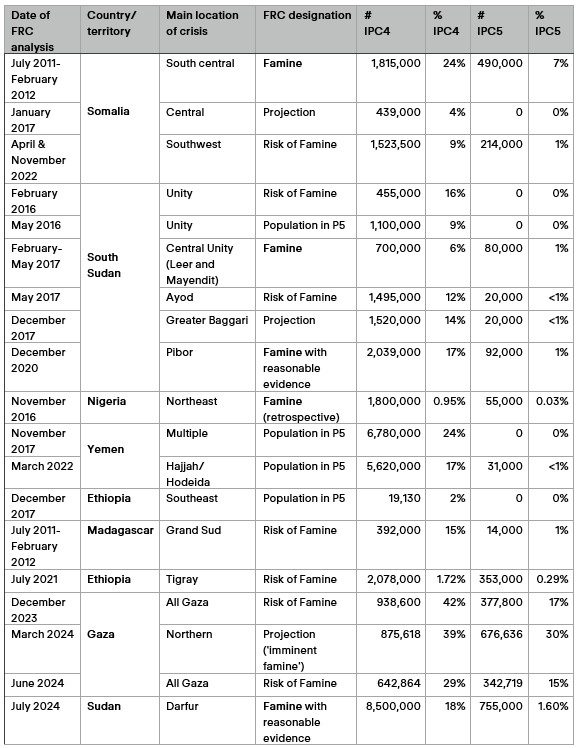

The following table includes all the relevant cases. Two points need to be borne in mind. The first is that there is no straightforward relationship between overall numbers of people in IPC 5 and the designation by the FRC. This is because the designation depends on the geographical distribution of those people and the trajectory of the crisis. The second, not covered in the table, is that in all cases the majority of those who die do so in IPC 4 rather than IPC 5, simply because the numbers are much larger, and they are in this phase for longer.

Table 2: Cases considered by IPC Famine Review Committee, 2014-2024, plus Somalia 2011

The figures can be further broken down by territorial subunits (e.g. administrative districts, governorates) within each country or territory.[26] Using these data, we can assess each case by using measures of magnitude and severity. For the purposes of this exercise, ‘magnitude’ refers to the highest total number of people in each phase in the affected country during the episode under consideration, and ‘severity’ is a measure of the proportion of the population in the worst-hit territorial subunit at the depths of the emergency.[27]

The following graph shows IPC 4 and 5 combined, with magnitude (in absolute numbers) along the horizontal axis and severity (in percentage of the total population in the locality) on the vertical axis. It will be clear that Sudan and Yemen are the largest crises by magnitude, but Gaza is the most severe. Cases in which IPC 5 ‘famine’ was determined are in red.

Figure 1: Recent Humanitarian Emergencies (IPC 4 and 5 combined)

Source: IPC population tracking tool. Magnitude measured by absolute numbers. Severity measured by the proportion of the population in the worst-hit locality (territorial subunit) at the worst time. The territorial subunits utilized are the smallest presented in the IPC datasets.

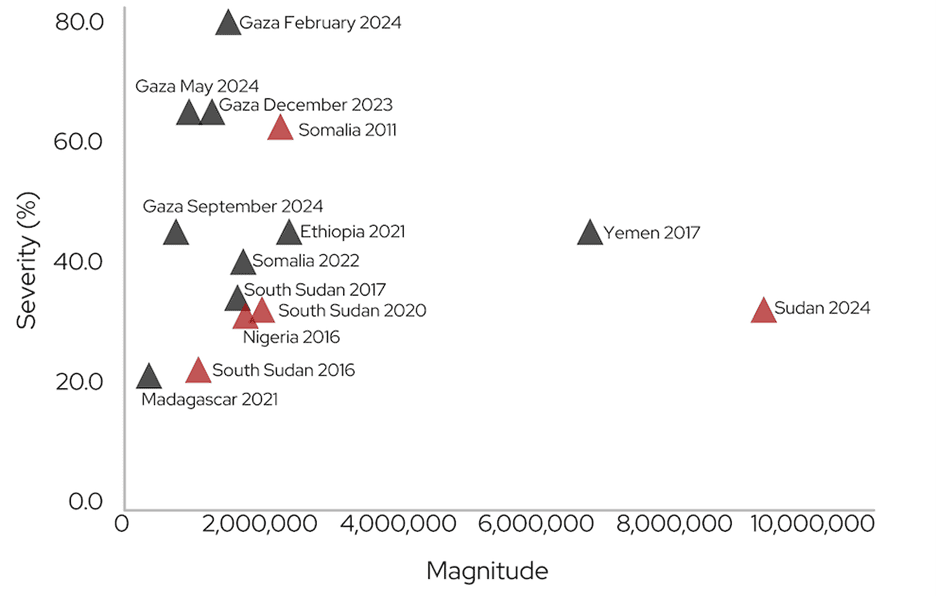

The following graph repeats this exercise but for IPC 5 (‘catastrophe’) only. Sudan is again the largest by magnitude, but it is closely followed by Gaza, which is again the outlier in terms of severity.

Figure 2: Recent Humanitarian Catastrophes (IPC 5)

Source: See figure 1.

No mortality projections can reliably be derived from these comparisons. However, given that the excess mortality in every one of the cases (bar Madagascar) has been in the tens or hundreds of thousands, it is plausible to infer that Gaza will not be an exception if today’s catastrophe is permitted to continue to unfold.

Timing: Sequencing and Trajectory Comparison

Mortality from starvation and health crisis unfolds over time. This means that many variables can intervene between the shock (violent deaths, forced displacement, destruction of objects essential for survival) and the outcome in terms of non-trauma mortality. Among those variables is the provision of relief assistance.

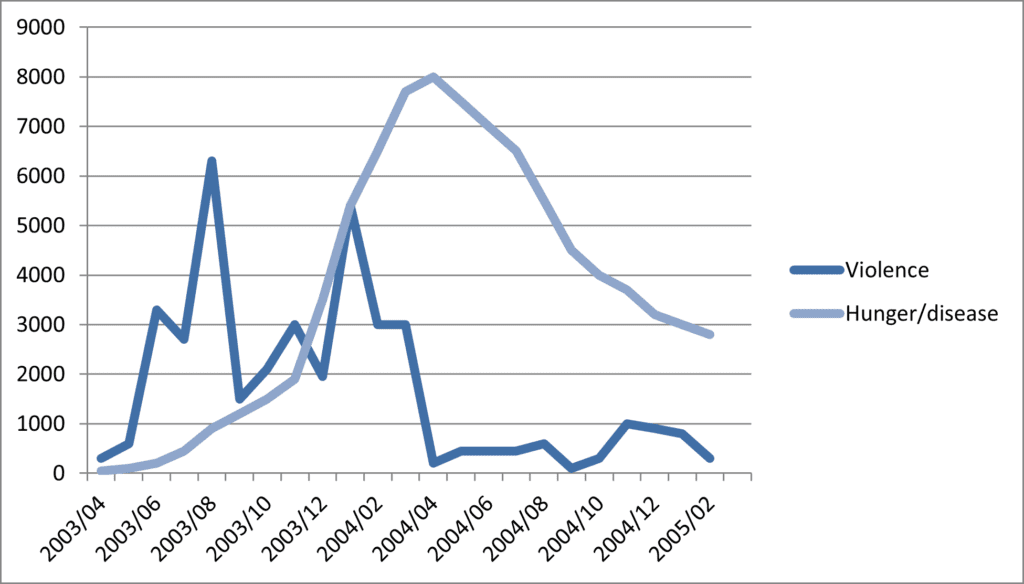

The case of Darfur, 2003-05, provides a useful comparison for addressing the question. The sequencing and trajectory of direct and indirect mortality is well-documented for Darfur, as illustrated in the following graph.[28] The figure also provides an illustration of how the direct:indirect ratio increases over time.

Figure 3: Violent fatalities and hunger/disease deaths in Darfur, 2003-05

Source: De Waal, 2002, utilizing data in Guha-Sapir & Degomme, 2005a, 2005b.

The sharp decline in violent deaths in April 2004 coincided with a ceasefire agreement and a major increase in humanitarian assistance.[29] The timing of the expanded aid effort was fortuitous, because the remoteness of Darfur and the severe logistical challenges in providing aid meant that food aid procured six months earlier began arriving in the region just as the ceasefire and opening of aid corridors came into effect.

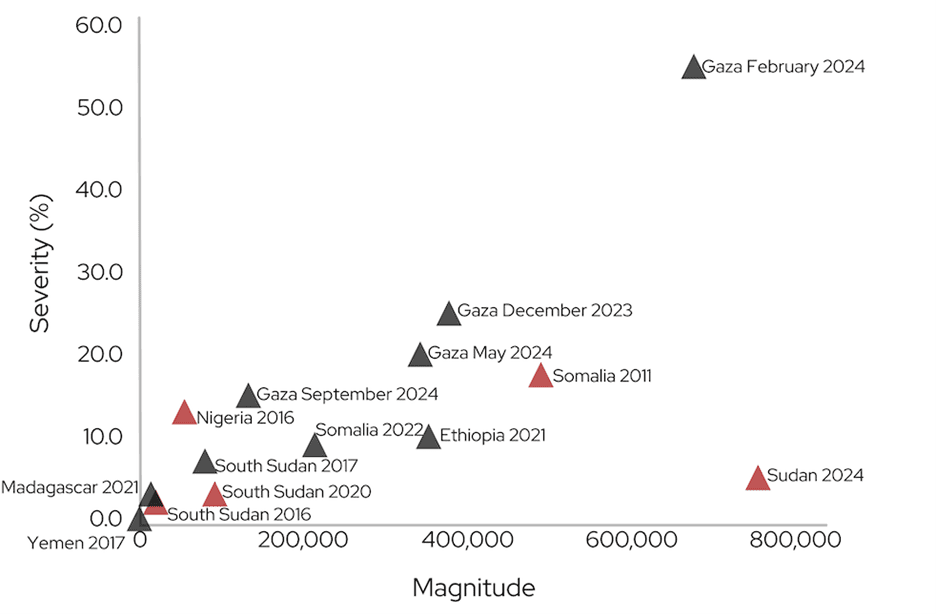

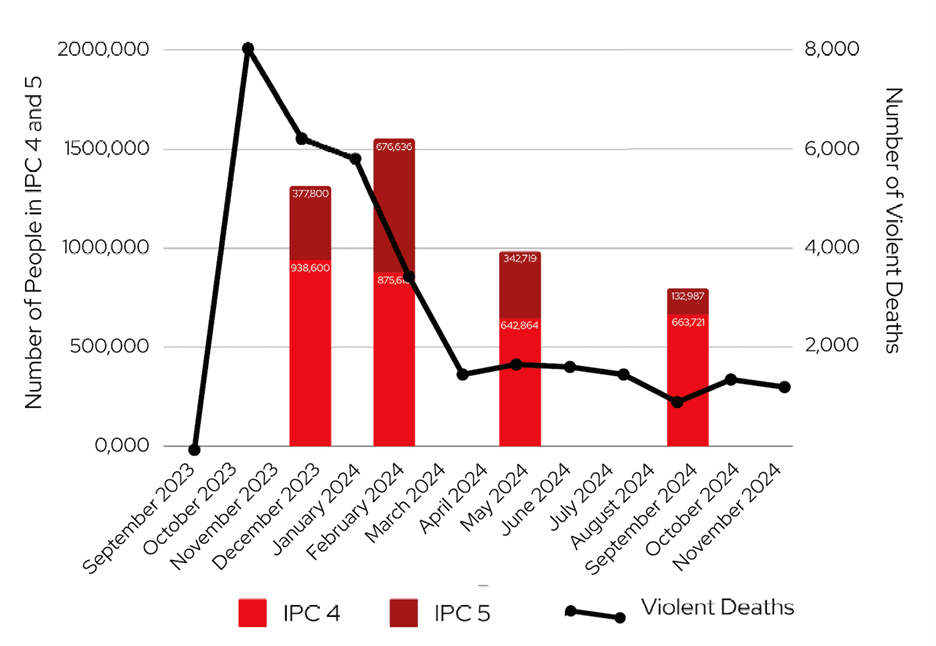

The sequencing and trajectory of the Gaza crisis appear to follow a similar pattern. The following figure uses the numbers of people in IPC 4 and 5 combined plotted alongside the numbers of violent deaths.

Figure 4: Violent fatalities and numbers in IPC 4 & 5 in Gaza 2023-24

Sources: Gaza MoH (WHO, OPT Emergency Situation Updates) and IPC.

The decline in the numbers of people in IPC 4 and 5 corresponds with the increased delivery of humanitarian assistance, which occurred in mid-March. On this occasion, assistance levels to the Gaza Strip fluctuated on a weekly basis depending on decisions made by the Israeli authorities, and the short distances meant that the impacts could be immediate.

The approximate correspondence between the sequencing and trajectory of the two cases is suggestive. However, it does not constitute firm evidence that non-trauma mortality has followed the same pattern. It may well be that the increase in assistance in March, that immediately reduced numbers in IPC 4 and 5 prevented escalating mortality levels at that time.

Conclusion

As explained in this blog post, the available datapoints cannot be used to derive accurate estimates of mortality attributable to starvation and health crisis/social disruption. However, it will be evident that they give no solace to those who seek to downplay the severity of the catastrophe. Absence of reliable data for starvation deaths is not a reliable datapoint for the absence of starvation deaths.

The balance of credible evidence and analysis does not support reassuring claims that seek to minimize the level of excess deaths due to individual and mass starvation.

Everything we know about the impacts of starvation and risks of mortality in famines points to the enormous significance of societal disruption. The role of humanitarian response, including food aid, is not only to provide calories but to prevent devastating health crises, destitution and social trauma.

In a court of law, a defendant should be presumed innocent until found guilty. In diagnosing a humanitarian disaster, the specialist may legitimately adopt the precautionary principle, finding that the population is in a critical state until proven otherwise.

The onus is on Israel to permit rigorous, independent assessments of the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza.

References

Akroyd, W.R., 1971. ‘Definition of different degrees of starvation,’ in Blix, G., Y. Hofvander, & B. Vahlquist, (eds.) Famine. A symposium dealing with nutrition and relief operations in times of disaster. Stockholm: Swedish Nutrition Foundation, pp. 17-24.

Alrashid Alhiraki O., Fahham, O., Dubies, H.A., et al., 2022. ‘Conflict-related excess mortality and disability in Northwest Syria.’ BMJ Global Health,’;7:e008624. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008624

Bang, F. B., 1978. ‘Famine Symposium: The role of disease in the ecology of famine.’ Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 7: 1-15.

Checchi, F., & Courtland, W., 2013. ‘Study Report: Mortality among populations of southern and central Somalia affected by severe food insecurity and famine during 2010-2012.’ Rome, FAO.

Checchi, F., et al., 2019. ‘Estimates of crisis-attributable mortality in South Sudan, December 2013-April 2018: A statistical analysis,’ London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Checchi, F., 2024. ‘Review of working paper by Fliss Isakov et al. on food aid to Gaza,’ 27 May, https://gisha.org/UserFiles/File/LegalDocuments/HCJPetition2024/LegalOpinionfchecchi27052024.pdf

Checchi, F., Ververs, M. & Jamaluddine, Z., 2024. ‘Wartime food availability in the Gaza Strip, October 2023 to August 2024: a retrospective analysis,’ (pre-print) https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.10.21.24315753v1

Degomme O, & Guha-Sapir D., 2010, ‘Patterns of mortality rates in Darfur conflict.’ The Lancet. 23;375(9711):294-300.

de Waal, A., 1987, ‘The perception of poverty and famines.’ International Journal of Moral and Social Studies, 2(3), 251-62.

de Waal, A. 1989, ‘Famine mortality: a case study of Darfur, Sudan 1984-5.’ Population Studies 43.1: 5-24.

de Waal, A., 2002., ‘The Conflict in Darfur, Sudan: Background and Overview,’ Testimony to International Criminal Court, The Prosecutor v. Ali Muhammad Ali Abd-Al-Rahman (“Ali Kushayb”): Situation in Darfur, Sudan, April 2022.

Dyson, T. & Ó Gráda, C. (eds.) 2002. Famine Demography, Perspectives from the past and present, Oxford University Press.

FEWS NET, 2016. ‘A Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State,’ Special Report, December 13. https://fews.net/west-africa/nigeria/special-report/december-2016

Fliss-Isakov, N., Nitzan, D., Magnazi, M.B., Mendlovic, J., Preis, S.A., Twig, G., Troen, A.M. & Endevelt, R., 2024. ‘Nutritional Assessment of Food Aid Delivered to Gaza by land and air drops, during the 2024 War.’ (Pre-print dated June 6, 2024; editorial decision ‘major revision’, no revisions available to online version as of December 14, 2024). https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4454344/v1

Foege, W.H., 1971. ‘Famine, Infections and Epidemics,’ in in Blix, G., Y. Hofvander, & B. Vahlquist. (eds.) Famine. A symposium dealing with nutrition and relief operations in times of disaster. Stockholm: Swedish Nutrition Foundation, pp. 64-73.

Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit—Somalia, 2011. ‘FSNAU Technical Series Report No VI. 46: Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Post Gu 2011,’ https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/fsnau-technical-series-report-no-vi-46-food-security-and-nutrition-analysis-post-gu

Gaasbeck, T., 2024a. ‘From Catastrophe to Famine: Immediate action needed in Sudan to contain mass starvation.’ Clingendael Institute, Alert, February.

Gaasbeck, T., 2024b. ‘Sudan: From hunger to death: An estimate of excess mortality in Sudan, based on currently available information,’ Clingendael Institute, Alert, May.

Gaasbeck, T., 2024c. ‘The silent catastrophe: Sudan’s continuing hunger crisis,’ Clingendael Institute, Analysis, November.

GAO (US Government Accountability Office), 2006. ‘Darfur Crisis: Progress in Aid and Peace Monitoring Threatened by Ongoing Violence and Operational Challenges,’ Washington DC, GAO 07/09, November.

Geneva Declaration Secretariat, 2015. Global Burden of Armed Violence 2015: Every Body Counts. Cambridge University Press.

Guha-Sapir, D., & O. Degomme, 2005a. Darfur: Counting the Deaths: Mortality estimates from multiple survey data. Brussels: CRED, May.

Guha-Sapir, D., & O. Degomme, 2005b. Darfur: Counting the Deaths (2): What are the trends? Brussels: CRED, December.

Hagopian, A., Flaxman, A., Takaro, T., et al. 2013, ‘Mortality in Iraq associated with the 2003-2011 war and occupation: findings from a national cluster sample survey by the university collaborative Iraq Mortality Study.’ PLoS medicine 10.10: e1001533.

Human Security Report, 2011. Human Security Report 2009/2010: The causes of peace and the shrinking costs of war, Oxford University Press and Simon Fraser University.

IPC Population Tracking Tool, nd. https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/population-tracking-tool/en/

IPC, 2016. ‘IPC Global Emergency Review Committee (IPC ERC): Conclusions and Recommendations on the FEWSNET IPC Compatible Analysis for Borno, Nov 2016.’ 6 December.

Jamaluddine, Z., Chen, Z., Abukmail, H., et al. 2024. ‘Crisis in Gaza: Scenario-based health impact projections. Report One: 7 February to 6 August 2024. London, Baltimore: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Johns Hopkins University.

Jawad, M., Hone, T., Vamos, E. P., Roderick, P., Sullivan, R., & Millett, C., 2020. ‘Estimating Indirect Mortality Impacts of Armed Conflict in Civilian Populations: Panel regression analyses of 193 countries, 1990-2017.’ BMC Medicine, 18(1), 1-11.

Khatib, R. et al., 2024. ‘Counting the dead in Gaza: difficult but essential,’ The Lancet, 404/10449, 237-238.

Levy, B. S., & Sidel, V. W., 2016. ‘Documenting the Effects of Armed Conflict on Population Health.’ Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 205-218.

Maxwell, D., Khalif, A., Hailey, P. & Checchi, F., 2020. ‘Determining Famine: Multi-dimensional analysis for the twenty-first century.’ Food Policy, 92, p. 101832.

Mordechai, L, 2024 ‘Bearing Witness to the Israel-Gaza War,’ December 5 (version 6.5.5)

Roberts, L., Zantop, M., Ngoy, P., Lubula, C., Mweze, L. & Mone, C., 2003. ‘Elevated Mortality Associated with Armed Conflict—Democratic Republic of Congo, 2002.’ JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(22).

Roberts, L., et al. 2004, ‘Mortality before and after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: cluster sample survey,’ The Lancet, 364/9448, 1857-1864

Sen, A. 1981. Poverty and Famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Sevall, S., 2023. ‘How Death Outlives War: The Reverberating Impact of the Post-9/11 Wars on Human Health,’ Brown University, Watson Institute, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2023/Indirect%20Deaths.pdf

Sidhwa, F., 2024. ‘65 Doctors, Nurses and Paramedics: What We Saw in Gaza,’ New York Times, October 9. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/10/09/opinion/gaza-doctor-interviews.html

Sidhwa, F., et al. 2024. ‘Open Letter from American Medical Professionals who Served in Gaza,’ (to President Biden), October 2. (Appendix) https://www.gazahealthcareletters.org/usa-letter-oct-2-2024

Spagat, M., 2024. ‘Tracking Gaza’s war death toll: Ministry of Health improves accuracy in latest casualty report.’ Action on Armed Violence, September 24, https://aoav.org.uk/2024/tracking-gazas-war-death-toll-ministry-of-health-improves-accuracy-in-latest-casualty-report/

Spagat, M., Mack, A., Cooper, T., & Kreutz, J. 2009. Estimating War Deaths: An Arena of Contestation. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 53(6), 934-950.

Spagat, M., & van Weezel, S. 2017. ‘Half a million excess deaths in the Iraq war.’ Research & Politics, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017732642

Stamatopoulou-Robbins, S., 2024. ‘The Human Toll: Indirect Deaths from War in Gaza and the West Bank, October 7, 2023 Forward,’ Brown University Watson Institute, Costs of War Project, October.

Tapp, C., Burkle, F.M., Wilson, K. et al. 2008. ‘Iraq War mortality estimates: A systematic review.’ Conflict & Health 2.1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-2-1

University of Washington, 2013. ‘Study: Nearly 500,000 perished in Iraq war. University of Washington.’ http://www.washington.edu/news/2013/10/15/study-nearly-500000-perished-in-iraq-war/

Wagner, Z., Heft-Neal, S, Bhutta, Z., Black, R., Burke, M., & Bendavid, E., 2018. ‘Armed conflict and child mortality in Africa: a geospatial analysis,’ The Lancet, 392/10150, 857-865.

Warsame, A., Frison, S., & F. Checchi, F., 2023. ‘Drought, armed conflict and population mortality in Somalia, 2014-2018: A statistical analysis.’ PLOS Global Public Health 3.4: e0001136.

Watson, O., et al., 2023. ‘Mortality patterns in Somalia: retrospective estimates and scenario-based forecasting.’ London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, February.

WHO, 2024a. ‘OPT Emergency Situation Update 33’, 6 June. https://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/Sitrep_-_issue_33.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

WHO, 2024b. ‘OPT Emergency Situation Update 52’, 4 December

Young, H, & S. Jaspars. 1995, ‘Nutrition, disease and death in times of famine.’ Disasters 19.2: 94-109.

[1] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Article 8(2)(b)(xxv).

[2] Sen, 1981, p. 1. Emphasis in original.

[3] Ackroyd, 1971, p. 18; See also: de Waal, 1989; Young & Jaspars, 1995.

[4] Bang, 1978; Dyson & O’Grada, 2002.

[5] Foege, 1971, p. 66.

[6] See: Alrashid Alhiraki et al., 2022.

[7] Roberts et al., 2004; Tapp et al., 2008; Hagopian et al., 2013; University of Washington, 2013; Spagat & van Weezel, 2017; Sevall, 2023.

[8] Degomme & Guha-Sapir, 2010.

[9] Spagat et al., 2009; Geneva Declaration Secretariat 2015; Levy & Sidel, 2016; Wagner et al., 2018; Jawad et al., 2020; Sevall, 2023.

[10] Roberts et al., 2003.

[11] Additional methods, such as remote monitoring of cemeteries, have been developed for use in Yemen and Sudan, and are useful in triangulating datapoints.

[12] WHO 2024a.

[13] WHO 2024b.

[14] Feroze, 2024.

[15] Maxwell, Khalif, Hailey & Checchi, 2020 (section 4.2); see also: Checchi & Courtland, 2013; Checchi et al., 2019; Warsame, Frison, & Checchi, 2023; Watson, 2023.

[16] Sidhwa et al., 2024. See also: Stamatopoulou-Robbins, 2024, who added an additional 5,000 deaths attributable to non-communicable diseases.

[17] For the case of Sudan, see: de Waal, 1987; Gaasbeck 2024a, 2024b, 2024c.

[18] Fliss-Isakov et al., 2024. The paper is a pre-print. The editorial decision was ‘major revision’ in June 2024. At the time of writing no revised version has yet been made available.

[19] Checchi, 2024.

[20] Checchi, Ververs & Jamaluddine, 2024.

[21] Jamaluddine et al. 2024.

[22] WHO 2024b, noting the review of the accuracy of the figures by Spagat, 2024 and assessment of the critiques by Mordechai, 2024, pp. 79-82.

[23] United Nations Population Division Data Portal, search terms ‘State of Palestine’ and ‘crude death rate,’ https://population.un.org/dataportal/home?df=96e5a7fb-4c53-4e61-8ca2-52da89b23233. The figure reported ranged between 3.0 and 3.8.

[24] IPC nd.

[25] Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit-Somalia, 2011.

[26] The data for this are not presented here but are available on the IPC population tracking tool site, IPC, nd. For the Nigeria case, the IPC 4 and 5 baseline population was assumed to be Borno State and the IPC 5 baseline population the numbers in IDP concentrations as assessed by FEWSNET 2016, p. 12. See IPC 2016.

[27] The subunits used are those of territorial units in the IPC population tracking tool. These vary in size.

[28] Note that the number of direct deaths in Darfur during this period was approximately 35,000, which is the same order of magnitude as the numbers in Gaza over a similar time period.

[29] GAO, 2006.